The Joshua Tree must be more than an album. And pondering its impact on me for its 30th birthday, this is more than just another mid-life crisis and exercise in nostalgia. 1987 was such a whirlwind year. 1986 and 1988, too. I graduated high school, started college, dropped out of college. I was finding myself and losing myself.

My first wave (1983-1988) of seriously following U2 would peak when I caught numerous shows that spring season, trekking around on the first leg of the North American tour, from Tempe to Los Angeles, from San Francisco and Detroit. My friendship with Maria McKee and Lone Justice, who would be tapped to open the shows on this tour, helped make this possible for a college student on a budget, as her generosity provided me guestlist tickets to the shows I attended.

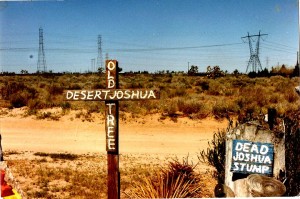

The Lenten season had just begun when the album was first released, so the record’s desert Biblical tones seemed more than a perfect fit for the journey we were on. That March, I scrambled to throw together my dream of following the band’s world tour. If people could follow Springsteen or the Dead, then U2 needed that kind of traveling fanbase, too.

At the time, I was living in intentional Christian community in Atlanta, and the idea of running off to catch these shows seemed frivolous, even a decadent privilege, but I was possessed in my gut with that kind of fandom obsession only conjured by rock n roll bands. Within walking distance of where I lived, I could purchase the new tape for less than ten dollars, and I learned all the songs by listening to it on my cassette Walkman with headphones.

The social frame surrounding The Joshua Tree was for me more-than-intense, a fierce urban and rural religious resistance to Reagan-era America. We could feel it from the breathing bricks and overgrown weeds of our lives, manifest in mixtapes of classic rock. I was running from rally to protest, against the KKK or against intervention in Central America or against apartheid in South Africa or against the nuclear arms race. We had a lot to be against. Because of all this passion, I decided my touring with U2 needed a “mission statement,” so I conjured up “Celebration Road” as the nickname for my endeavor. I would pass out fliers at the shows, encouraging fans to get involved in movements for change.

Like the social and political edges, the musical ambiance that influenced The Joshua Tree also influenced me in heady and heavy ways. Like Bono and the gang in their late 20s, during my last days as a teenager, I rediscoverd the deeper cuts in the music of the late 1960s, music that had been on the turntables at my house my whole life. And after being mostly straightedge in high school, I was suddenly discovering the substances that made the 60s sound better. Like Bono has said about himself in the intervening years, I was as much punk as hippy. But so much both, that at times, I had been called hippypunk. For my sensibilities, U2 and R.E.M. of the late 1980s were much more avant-garde in musical and political spirit than their sudden “college rock” surge in popularity might suggest.

As much as I loved learning more Dylan or more Doors, more Beatles or more Hendrix, I could easily fall into rapturous moments with the Minutemen or the Meat Puppets or even hardcore like M.D.C. or Dead Kennedys.

Looking back, this time would be the last season of my youth when I would identify as a follower of Christ, before a two-decade descent into a crazed wilderness of addiction. My belief in Jesus had shaped, inspired, and guided me for so long, that it was hard to imagine life outside church and fellowship communities. My faith filled me with passion, and it shaped the entirety of my life, fueling my commitment to social justice. But the allure of the secular counterculture called loudly. I found myself dancing in the streets, debating in classrooms, and drinking at parties, seeking and craving and experiencing a version of the revolution that wasn’t rooted in a religious context.

Listening then and listening today, The Joshua Tree reaches the status of canon and brings a riveting liturgical experience. This is rock as revelation. The tracklisting is an order-of-service. Strangely, my experience of immersion on the opening leg of the tour would almost completely sate me. These concerts were undoubtedly church, but I would get somehow and somewhere disillusioned by the end of the line, and I was ready for extended visits to other rock-and-roll denominations. Months later, I would get spiritually restless, and some of the theological significance of the album for me would get lost, at least for awhile. Nevertheless, I have returned to this record at various times and places, and it has been rock scripture again and again, unpacking parts of my aching heart in new ways.

I stopped listening to U2 as much when I drifted away from Jesus. Then, when I made a decisive break with the church at 20 years old on Easter 1988, it was to listen to loud voices of hedonism, psychedelic and otherwise. When I returned to U2 in the 2000s, to this album along with all the others, especially All That You Can’t Leave Behind and How To Dismantle An Atomic Bomb, U2’s music helped draw me back to the source of my faith, the source of salvation, to Jesus.

U2 has always embodied for me what we today call the intersectional, the deeply connected. For them, the message is musical art as justice, brandishing a chorus or a guitar solo at that crossroads of God and spirituality, at the intersection of romantic love and movements for social change.

The music that a person connects with while growing up is the music that grabs heartstrings and holds you with gravity. To this music you can return, years and years later. My yearning for deep spirituality and romantic love and world peace were the swirling turbulence of the late 1980s, and this album brings those aches a profound amplification. Older versions of ourselves share the same concerns, and we will sing them out loud on this coming tour.

reposted from U2interference.com

No comments:

Post a Comment